Everything I Think About When Drafting NFL Best Ball Teams

There have been five best ball seasons on Underdog Fantasy, encompassing millions of teams drafted over different slates. While each season of games and each draft season of ADPs will tinker with the specific results, we are getting closer to a consensus on the general best strategies to be used in the NFL best ball streets. This column is my top-down view of the most important things to consider when drafting, with the most important concepts at the very top of the column.

If you're new to best ball, here is a promo link to use to sign up and get some bonus cash for playing on Underdog Fantasy. We are home to $15M Best Ball Mania, $1.7M Weekly Winners, $1.75M Eliminator, and countless other dog-punned tournaments. It's the place to play fantasy football. Give it a try on us.

1. Mastering Roster Construction

The most important thing to do in best ball is to invest in each position (QB, RB, WR, TE) at the correct weight. Any time a team invests too much of one position, the more wasteful that draft capital becomes. For example, drafting Lamar Jackson in Round 3, then Josh Allen in Round 4, and then Patrick Mahomes in Round 7 is guaranteeing a loss of potential points in each round as we can only start one QB each week. This is the law of diminishing returns.

Roster construction – the amount of players at each position in best ball – shouldn’t only be viewed as the total number of picks at the end of the draft, but it should be a sliding scale throughout the draft because players drafted earlier score more points, so the amount of expected points added to your team is higher early on. Duh. So how can we simplify the specifics of the diminishing returns of roster construction?

The correct answer is to study this column over and over again, but here is a quick recommendation in the early, middle, and final rounds:

The amount invested through Round 6 should be on the opposite side of the guideline through Round 18. For example, a team with 3 RBs through Round 6 (which is totally fine to do) ... should only have 5 RBs total, even though the table recommends 5 or 6 RBs total. The same is true through Round 10. A team with 5 WRs through Round 6 and 6 WRs through Round 10 should end the draft with 6 WRs. The team stayed within the recommended buckets throughout the draft and abided by diminishing returns.

Some other quick specific notes on roster construction:

There are ways to build good teams not within these buckets, but it’s a highly volatile strategy that requires a lot of game theory knowledge to pull off. We’ll get to uniqueness in a bit.

I don’t utilize zero RB much because the ADPs are so anti-RB right now, but I have a full Zero RB strategy column here.

The earliest a team should have a 2nd QB is in Round 8. The full column is here.

I invest more into QBs early in the offseason when I’m less sure of the projected points of RBs, WRs, and TEs before more news comes out during training camp and preseason.

2. Drafting Near ADP

Once we’ve locked in proper positional investment, the next step is making sure we don’t reach too far to fill those buckets. The average draft position (ADP) on Underdog Fantasy updates daily and is based on real-money drafts, and it’s a generally good tool for assessing value (with some exceptions). It’s also the default for teams that are on auto-draft, and there’s an effect that drafters are bullied into drafting players at or near the top of the default queue. That means most picks are generally close to best player available. Should that be the case?

Yes, and I have a full column on it here. Simply put, the top-performing teams draft most of their picks at or near ADP, and the teams that frequently reach 10+ spots above ADP are often the worst in the lobby, so a simple way to stay on track is to pick the earliest player in ADP that fits your roster construction from the first section. The difference between the 3rd and 4th best available players is negligible, but the difference between taking the player who has fallen 8 spots past the default ADP versus a drafter reaching on a player 8 before ADP is enough to hurt.

The other reason not to reach on ADP is because the player you are reaching for has a chance to be available at your next pick. In fact, I calculated the probability of a player being available based on how far they are from the ADP in this table here. Of course, we want to make sure we’re drafting “our guys” at reasonable price tags.

In the upcoming “uniqueness” section, I lay out some cases on when reaching is actually smart, but in general, drafters are reaching in ways that hurt their teams a lot more often than they are reaching in ways that are helping their teams.

3. Stacking the Right Teammates

If we invest an early pick on a player, we need to tell ourselves a story about how the pick pays off. Part of that story is often saying that the entire offense is going to play well, which is the core concept of stacking. Draft teammates. What is left off that discussion too often is ignoring how correlated certain teammates actually are. The strongest correlations are between QB-WR and QB-TE because the quarterback literally throws the football to the WR and TE. When a WR catches a touchdown, the QB gets points too. Duh!

Here’s a quick summary of how much correlation teammates have in a single game involving a spike week, with my full column on it here:

This is how it plays out on the average offense, but it’s important to note the type of offense each team uses, with an emphasis on the type of QB the team has. Teams with a dual-threat QB will typically have fewer receiving production available, so the correlation between QB1 and his WR2 is lower than it is with a pocket passer. Ironically, that means the best teams throughout NFL best ball have been team stacks built around pocket QBs — not dual-threats — tend to bring more teammates along for the ride.

General rules to follow with stacking:

QB to pass catcher correlation is the strongest.

Dual-threat QBs don’t need as much pass-catching stack partners.

RBs add some season-long correlation to teammates but don’t offer much in terms of single-game ceiling outcomes.

The type of RB matters to the stack. A pass-catching RB will correlate to a WR2 better because of the game script needed, where a goal-line RB will be highly negatively correlated to a touchdown-or-bust TE.

4. Having Sharp Player Takes

It’s helpful to know ball, and this 4th topic is the one that’ll be forever relevant and forever unsettled. In fact, it’s the part that will matter the most long term as most competitive drafters can learn topics 1-3 in this column very quickly. What will eventually settle the average to great drafter will be player takes and how to build teams around them.

What's fun about this is winning on player takes can come from different philosophies and and it’ll take years of feedback to know who actually has good player takes. A spreadsheet bro could theoretically have great player takes. A film bro could theoretically have great player takes, assuming they can translate their film takes into projections — even mental ones. To me, the best player take person would fully understand football, the player they are analyzing, the scheme they are playing in, and the depth chart surrounding the player. They’d also need to know the full fantasy player pool to understand which pockets of players they want to draft from, and they'd have to have some humility in roughly sticking with consensus, as that's proven to be a worthwhile barometer of value.

That's my personal goal here. Watch and understand as much football as possible for everyone involved in fantasy football, and then being able to concisely bring that information to the Underdog Fantasy YouTube Channel in a timely manner. Some things we're doing over there is film studies, analytics studies, NFL Draft videos, press conference clips, having on the best guests in the space, reacting to training camp news, updating fallers and risers in ADP, posting NFL trade reactions, and actually drafting some best ball teams to show how this all ties together.

What is fun is that this process is insanely hard to drill down with AI or tools or anything of the sort. Even the player projections that are available are manually inputted (if they are any good), which means the smartest projections still require knowing ball. If everyone ends up with a baseline of information on roster construction, stacking, ADP value, uniqueness, and the other topics in this article, then let the best player takes win.

That's a fun game to play.

5. Balancing Early and Late Season Production

Player takes are individual. Player pairings are relational. Now let’s look at how to build combos that don’t overlap in their strengths or weaknesses. The reality is some players fit better with other types of players, even if they aren't teammates or play each other all season long. A player who projects best in Weeks 1–4 pairs better with someone who peaks in Weeks 14–18, not another player who projects best in Weeks 1-4.

The radical example would be drafting a team entirely made up of rookies, who typically score the most fantasy points down the stretch after getting acclimated to the offense. We want to have some rookies, but we can't expect to advance out of the first round of best ball if they are the only players we have. Beyond rookies, other useful archetypes include aging veterans with young competition on the roster (better early), suspended players (usually better late), and players with weather concerns (usually better early).

To take this a step further, this issue mostly exists at the position level, not across entire teams. For example, figuring out which type of TE2 and TE3 to draft will depend on the archetype of the TE1. If our TE1 is rookie Colston Loveland, who may not play immediately behind Cole Kmet, then we probably don't also want contingent-based Isiah Likely as the TE2 and fellow rookie Harold Fannin as the TE3. That’s punting off too many early-season points, which will hurt our regular season advance rate odds. Likely with Fannin makes a lot more sense with T.J. Hockenson, who might project better early on if his teammate Jordan Addison is suspended in September.

6. Creating Uniqueness

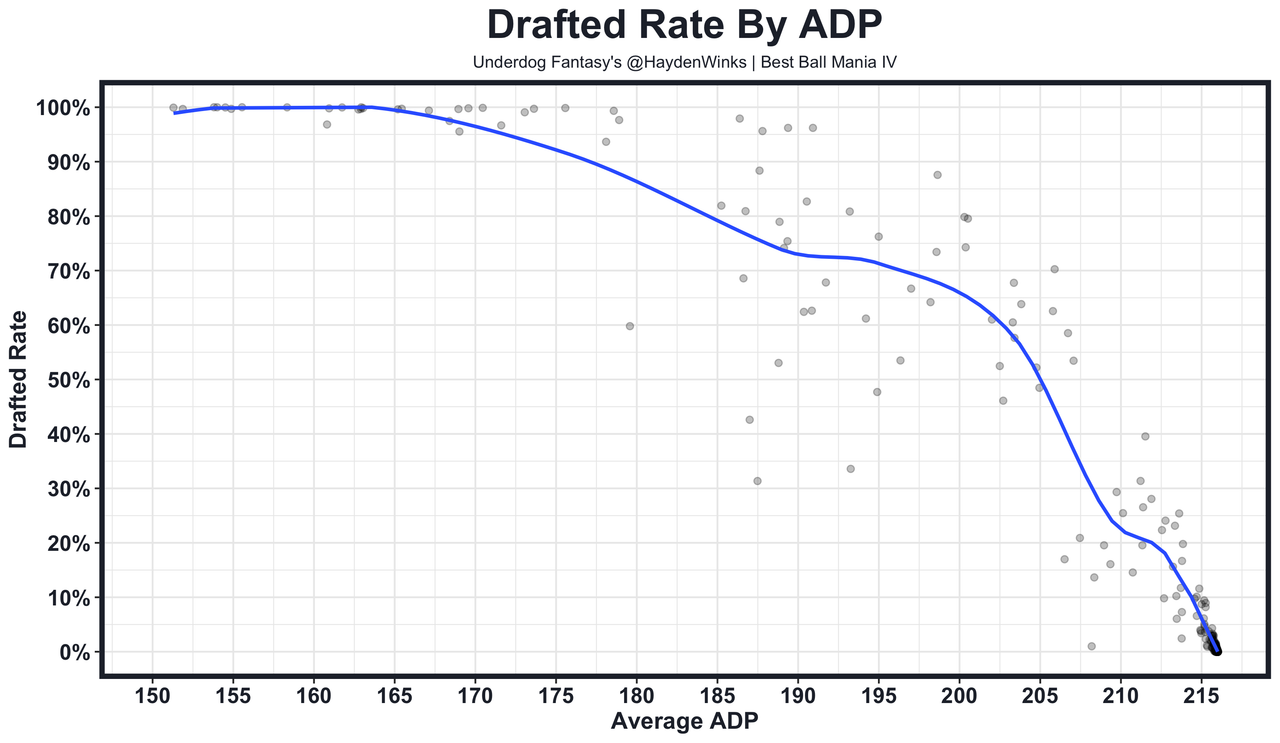

Zig while others zag is a way to create some leverage in peer-to-peer games. It's a bit more challenging to navigate in best ball where most players who are drafted are drafted in 100% of the other drafts in that tournament, but there are a couple sneaky ways to create some leverage by attacking less-drafted player combinations or by knowing when to draft a less-drafted player without sacrificing projected points.

The only way to get lower drafted rate players is by reaching for guys with an ADP of 200-216. Many of these players stink, so it does come with a cost. The best way to leverage this is by figuring out when players drafted in 100% of drafts don’t project that differently from those drafted in just 50% or fewer. From my research, that's been avoiding players with a 160-180 ADP (100% drafted but not good) and scrolling down to players with a 205-212 ADP (25% drafted but still in range to have some spike weeks). These are "reaches" by definition, but the market isn't very good with ADP this late into drafts and these are the equivalent of $1 auction values, so this is the time to know some ball.

The chart below showed how often other Round 1/2 turn players were drafted with Austin Ekeler, who was being drafted at the Round 1/2 turn himself back in 2021. Because Nick Chubb (12% paired), Calvin Ridley (10%), and Stefon Diggs (10%) were most commonly the best player available on these Ekeler teams, they were paired with him the most often. But these players didn't project all that better than let's say Najee Harris (4%) or A.J. Brown (1%), yet that combination was much less common. If Ekeler and Brown were the guys you needed that year, there's only competition with 1% of teams rather than if it was Ekeler and Chubb where the competition is still 12% of Ekeler teams. This combination theory is best suited early in the draft where there's less reaching from ADP, and it's best suited late in the drafting window when we know if these players' ADPs have stayed in the same spot or not.

Along these same lines is the concept of double-tapping the same onesie position in back-to-back rounds. In this uniqueness column, I have evidence that drafting a QB in Round 8 and Round 9 is very uncommon, and I'd wager to say it's the same at TE as well. The reason is because some of the teams drafting a TE in Round 9 already have another TE earlier, thus won't draft a TE3 in Round 10. I also think there's some psychology of feeling overexposed to a onesie if they were back-to-back selections. It's not a big deal all in all, but it's something to think about and a good example of the weeds you can get yourself into if you think hard enough about best ball... You can also touch grass and play for some life EV. That works even better.

My favorite way to use uniqueness is by combining roster construction with player archetypes. I studied what types of WRs and RBs teams who went Zero RB were drafting, and they were much different than the types of WRs and RBs teams who invested into RBs early were drafting. This held up even at the same ADPs later in the draft. As the bit would suggest, the Zero RB drafters loved the 198-pound pass catching RB2 while the Robust RB drafters were more likely to draft the older WR. If you go with a Zero RB build, but then draft the types of late-round RB profiles that an early RB bro would draft, then you've built a really unique team. This is especially true in 2025 when so many of the best ball influencers have the same general takes of Zero or Hero RB with an analytic preference on player takes.

7. Reading the Draft Room

We don't draft our teams isolated. We have to be paying attention to the teams being drafted next to us. This is especially true in a couple specific situations.

The first is when we’re picking near one of the turns — like 1.02/1.03 or 1.10/1.11. Later in the draft, we can re-calculate the odds that our targets make it back to us based on the construction of the teams out of 1.01 or 1.12. For example, if we want to complete a stack with a QB and we see that the 1.10 and 1.11 already each have 3 QBs, then we know we can wait until after the turn to grab that QB.

The other example is when a draft room is thinking similarly and a run on a position is starting way earlier than normal. For example, if one or two teams are obnoxiously drafting a bulk of the elite onesies, forcing the rest of the group into 3-QB or 3-TE builds, deleting positional depth. This also happens on streamed drafts in particular when the hosts have a distinct viewpoint on how to draft, forcing a run on the early and middle WRs earlier than usual. It also happens in the first weeks after the NFL Draft is over when rookies often hit their highest prices of the draft window.

Try to stay aware of what’s happening around you — especially when draft behavior deviates from the norm. And the solution could simply be to punt that position and scoop the value at other positions, while figuring out that position later with more depth. Remember, this is peer-to-peer. Zig ... Zag.

8. Chilling on Week 17 Bring-Backs

Bring Back Correlation is largely pairing a player with someone he's facing in Week 17, which is the best ball finals where we have millions of dollars up for grabs. But the definition of bring-back correlation is evolving, as many are valuing Week 16 (the semifinals) and Week 15 (the quarterfinals) now because, you know, you do have to advance beyond those crucial weeks to even get to the finals. For that reason, it's already hard to sweat about the bring back correlation because it requires advancing through three different rounds to get to Week 17, but it is a slight benefit in theory to have access to the shootout games of Week 17. There's no debating that part of it.

There are things ignored in these conversations, however. One, the bring back correlation isn't the same across positions. A TE and from the other team aren't very correlated as an example, so blindly clicking bring back correlated players while ignoring the amount of correlation is silly. The most correlated players are QBs and WRs, with the theory being one QB-WR pair scores a long TD incentivizing the other QB-WR pairing to throw the ball in catch up mode. In general, that's the best way to attack it.

The big problem with this is the rate at which drafters are pairing the bring back correlation. If every Ja'Marr Chase drafter is going to draft Trey McBride in late Round 2 (CIN vs. ARI in Week 17 this year), then there is a major leverage advantage to simply taking a different player instead of McBride there. This goes back to the 6th topic. Unfortunately, the bring back correlation is so small to begin with that when pairing rates spike, the correlation edge erodes quickly, and if it swings too far, then it's obviously +EV to fade the pairings altogether. I fear we are already at (or at least approaching) the latter part of this equation. It'd be a great research article for someone to investigate: the drafted rate of Week 17 pairings versus the gained points of the correlation. There's a hypothetical equilibrium. We just don't know it as a community yet.

All things held equal, I'd rather hunt for a 4th team to stack rather than finding bring-back correlation for my original stack. I'll take the added correlation in Week 1, Week 2, Week 3, and so forth to Week 17, rather than put my eggs into one basket when I might not even get to the dance.

9. Managing Player Exposure

How often we draft a player on a slate is almost entirely a risk tolerance preference and has no direct impact on whether the decision is +EV. If a drafter only wants to draft at most 15% of a player during the best ball season, great! If a drafter wants to draft 30% of a player, that could work as well! The higher the exposure, the higher risk. But risk doesn’t mean it’s good or bad.

The primary issue with a really high exposure is that a drafter is likely routinely reaching on that player to get him, and as we outlined earlier, that’s typically a bad move to make. To get 35% exposure to a player routinely drafted in Round 5, you’d often have to take him in Round 4, and that’s a dangerous game to play!

For me, I don’t mind having 25% or more of a player, but I’m likely to do so with a player whose ADP is at the end of the draft where reaching has a smaller (or nonexistent) consequence. The players I love early on are usually in the 18-24% range because I want to make sure to get my guys at or near ADP. In fact, it’s best when I can get a player I love after ADP, which will occasionally happen if you give it a chance.

Conclusion

There’s no perfect way to play best ball, but the best teams usually mix structure with a little controlled chaos. If you can stick to good roster construction, draft near ADP, stack smartly, and add a couple of your own player takes or combos, you’re doing better than most of the lobby. After that, it’s just about putting in the reps, running hot, and letting your edges show up over time.

Good luck out there — and let the best player takes win.